On Toiling and Process

The Venice Biennale recently named the 332 artists who will participate in their 2024 edition. 52% of those artists are dead. A new high, apparently.

Why can’t we acknowledge more artists while they’re alive?

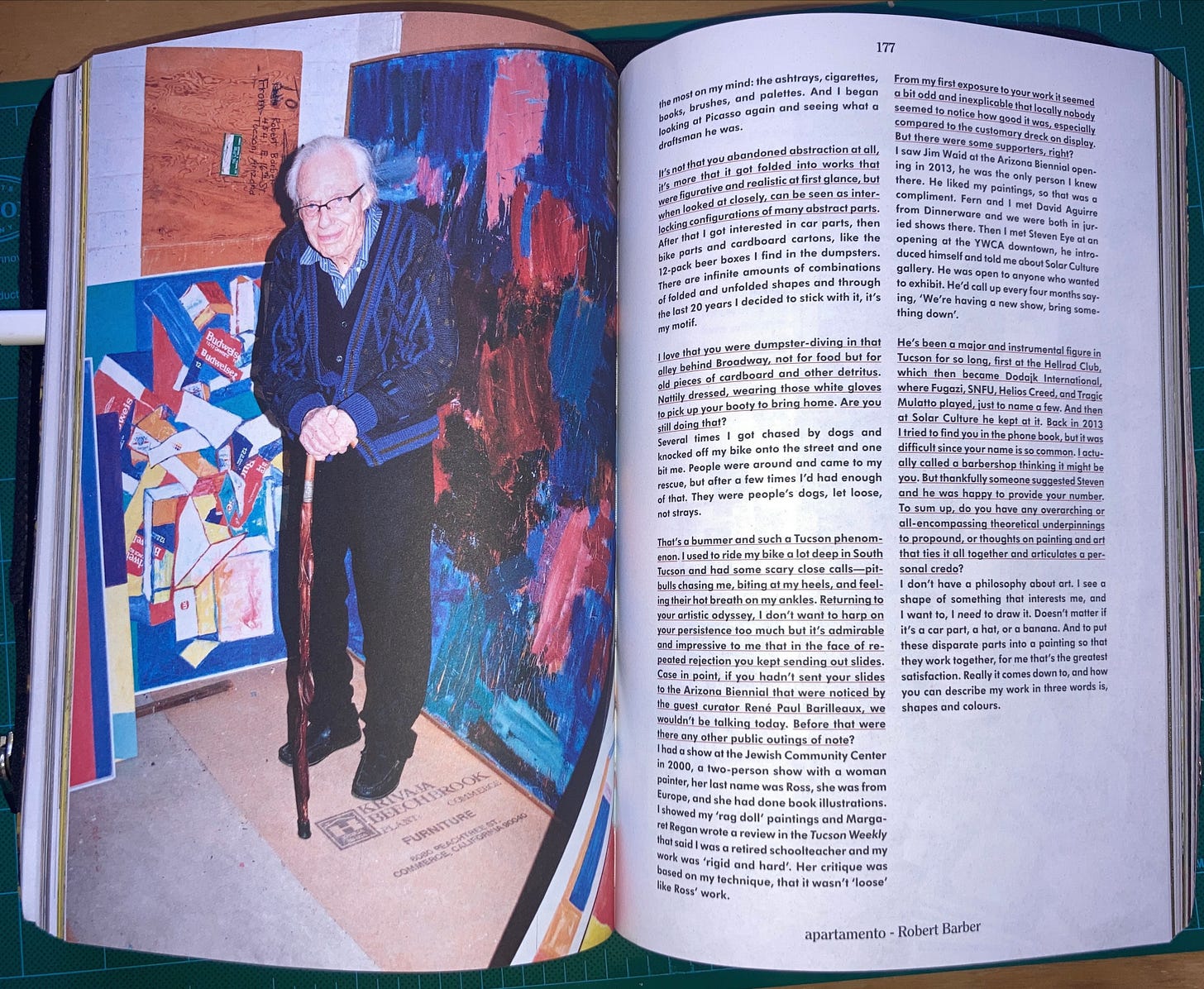

In a recent issue of Apartamento I read about Robert Barber, an artist born in 1922 who only gained recognition from the art world in 2013. The interview with Jocko Weyland is vast, spanning a century of memory. It begins with this introduction:

Neglected, ignored, unknown, or unrecognized, the artist garnering little or no attention during their lifetime who nevertheless keeps plugging away is a common cliché, a stereotype covering the spectrum from those who toil in obscurity to be forgotten forever, which is normally the case, or the ones discovered and in some cases celebrated posthumously. Very small chance of fame in the afterlife, or absolute nullity in death, either way it's a crap shoot. And adding insult to injury, the deceased artist frequently gets lauded in a way the complicated, perhaps cantankerous and irascible living version never would have been. Additionally, if their history involves anguish, psychic pain, excessive drinking, a messy personal life, and madness, the more attractive they are from beyond the grave. It's the way of the world.

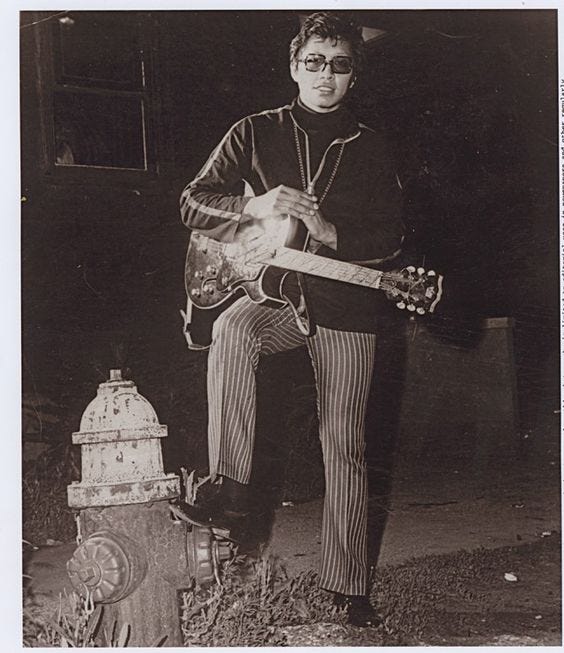

Around the same time I read that interview, I watched the 2012 documentary Searching for Sugar Man. It tells the story of Rodriguez, a Detroit musician whose music was completely unknown in the US - yet by way of timing and chance, and unbeknownst to him, massive in South Africa. It’s a magical story that unfolds before the internet was alive, when the only way to get to the bottom of a question was through research and phone lines and clues found in liner notes.

How does life change when one gets the recognition they deserve?

How does the work change?

How many will forever toil in obscurity?

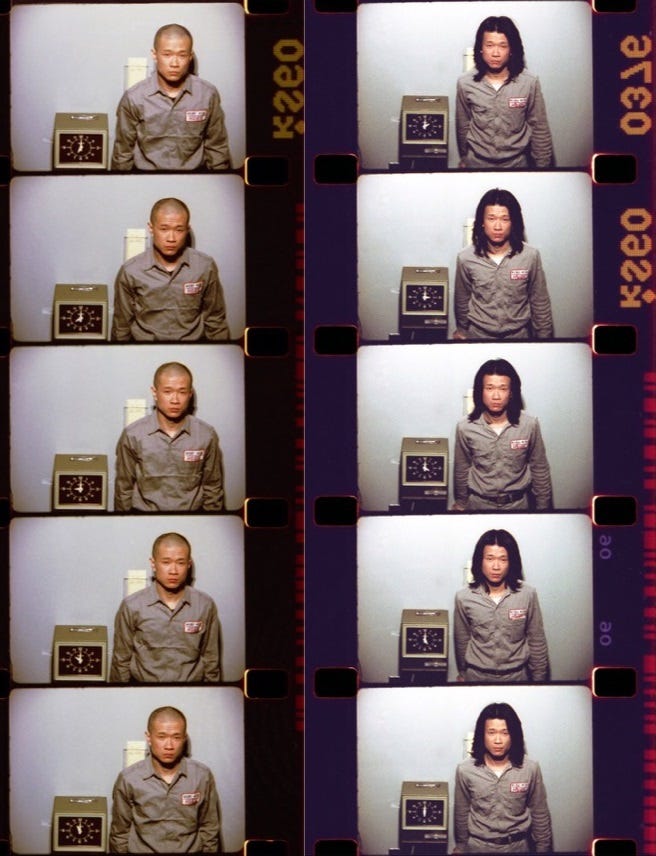

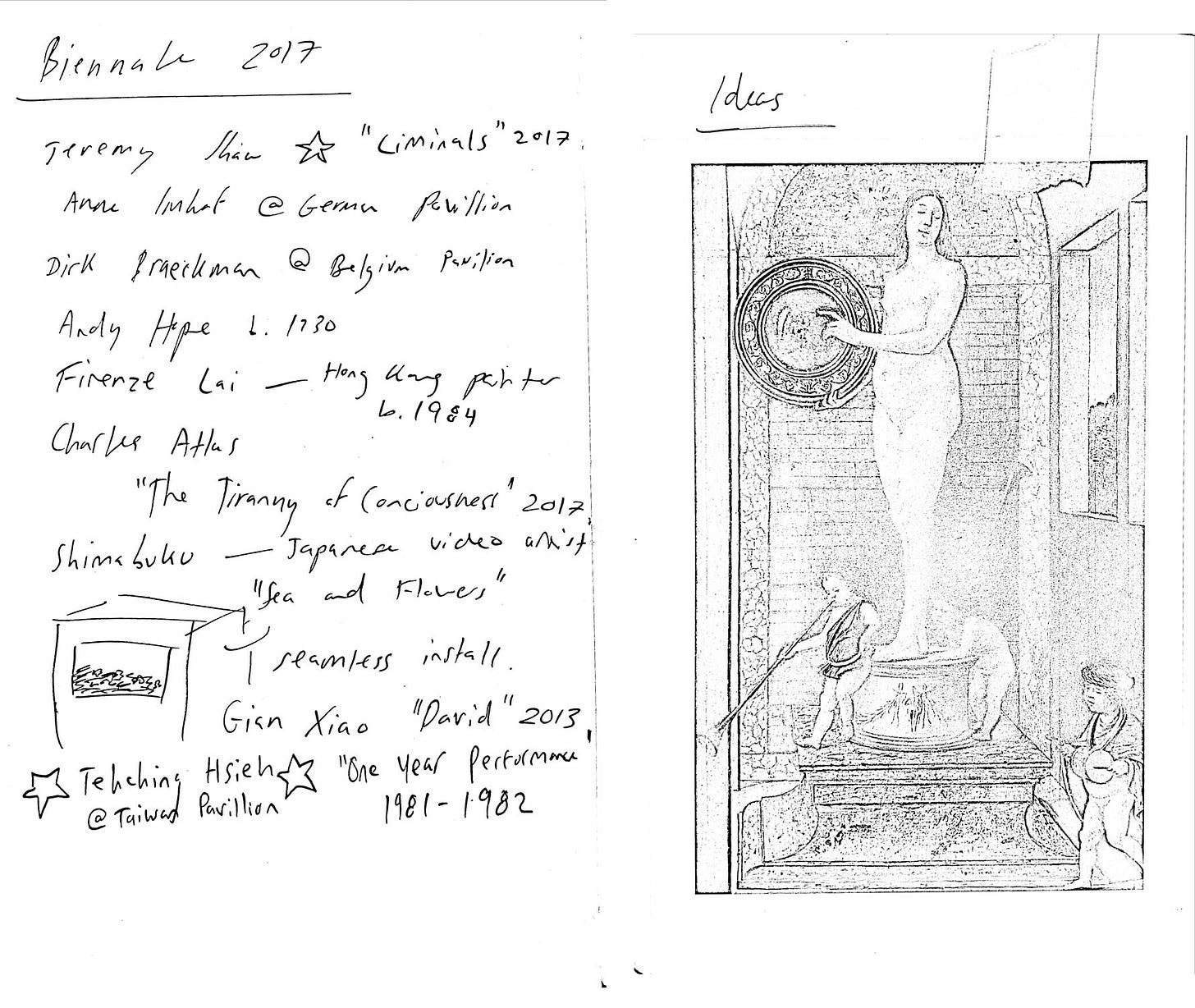

I visited the Venice Biennale in 2017. A few works have stayed with me: Liminals by Jeremy Shaw, the paintings of Hong Kong’s Firenze Lai, and the work of Taiwanese performance artist Tehching Hsieh. Hsieh’s work captivated me like no other performance art has ever come near to: work that relies on the passing of time, paired with the artist’s investment to see it through. Time Clock Piece sees Hsieh punching an office time-card every hour, 24 times a day, for a whole year; reorganizing his life around the process of documentation.

“One year is the basic unit of how we count time. It takes the earth a year to move around the sun. Three years, four years, is something else. It is about being human, how we explain time, how we measure our existence.”

Like Robert Barber, Hsieh’s work was almost lost. In 2009, 30 years after his first durational piece, his work found it’s way to the MoMA, then to the Guggenheim, then to the Taiwanese Pavillion for the 59th Venice Biennale. Hseih currently lives in Brooklyn.

I think a lot about time-based work, and see my own photographic work existing with that realm.

In November, I started renting at my current studio. My dream of having a big desk with a big white wall had come true, and I meticulously combed through my entire archive of images, making hundreds of 4x6” matte prints. I began to organize the images into various subjects: windows, shadows, cars, flowers, the natural world. It was amazing to see the breadth of my work physically in front of me; the same subjects returning again and again, my eye subtly evolving.

I imagine the wall in another 15 years: in the case of my ever-growing archive, time is a friend.

With two dedicated mediums, I think a lot about speed in relation to output– would I have accomplished more in photography if it weren’t for music? And vice-versa? These thoughts come to me in times of fear, when I feel as if I’m toiling in obscurity. And yet, I know that there would be no way for one to continue without the other.

So the archive grows. An image from 2011 is placed next to an image from 2022. A melody from 2018 makes its way into a new demo. The toiling is the process.

Next week I’m off to the UK, with 3 cameras and a zoom recorder in tow. There is a distinct urge to document this journey, even if I don’t know what the outcome from the collected material will be. I fall asleep imagining the sounds of the ships and the waves, of the mourning doves in the garden once tended by my grandparents, of the wind through the train car windows. Slowly, I begin to picture it.

I really enjoyed reading this Tess. I too think about time a lot, about how fast it slips by and yet how slowly it can drag itself out, about how not to wish it away when things are difficult and also not to assume that the good times will endlessly unfold.

The toiling really is the thing though whether in obscurity or in fame both of which can of course impact the process.

Thanks for writing about this.